.jpg)

April 2020 marked Fuzzy Labs’ first birthday. It also marked the start of a national lock-down in the UK owing to a worldwide pandemic—perhaps you’ve heard of it?

Before you close that tab, I promise this isn’t yet another “how to digitally transform your business for post-COVID enterprise buzzwording” article. Of course we had to adapt, but so did everybody else, so you all know what that’s like by now. Instead I want to tell you about our internal R&D project, Wearable My Foot, and share our journey into building data-powered wearables, a journey which just happens to include some unique logistical challenges otherwise known as the new normal (ugh! okay, I promise not to use those words again).

It’s a tale of hardware prototyping, data wrangling and software hacking, while working across two continents. All made possible by camaraderie, teamwork, solder and whiskey.

Pre-history

A little history first. The original plan was to detect a person’s posture when they stand still, walk, or run, and use this data to train an AI to decide if one’s posture is good or bad. Besides that, this device could collect metrics for the user’s activity, such as steps or speed.

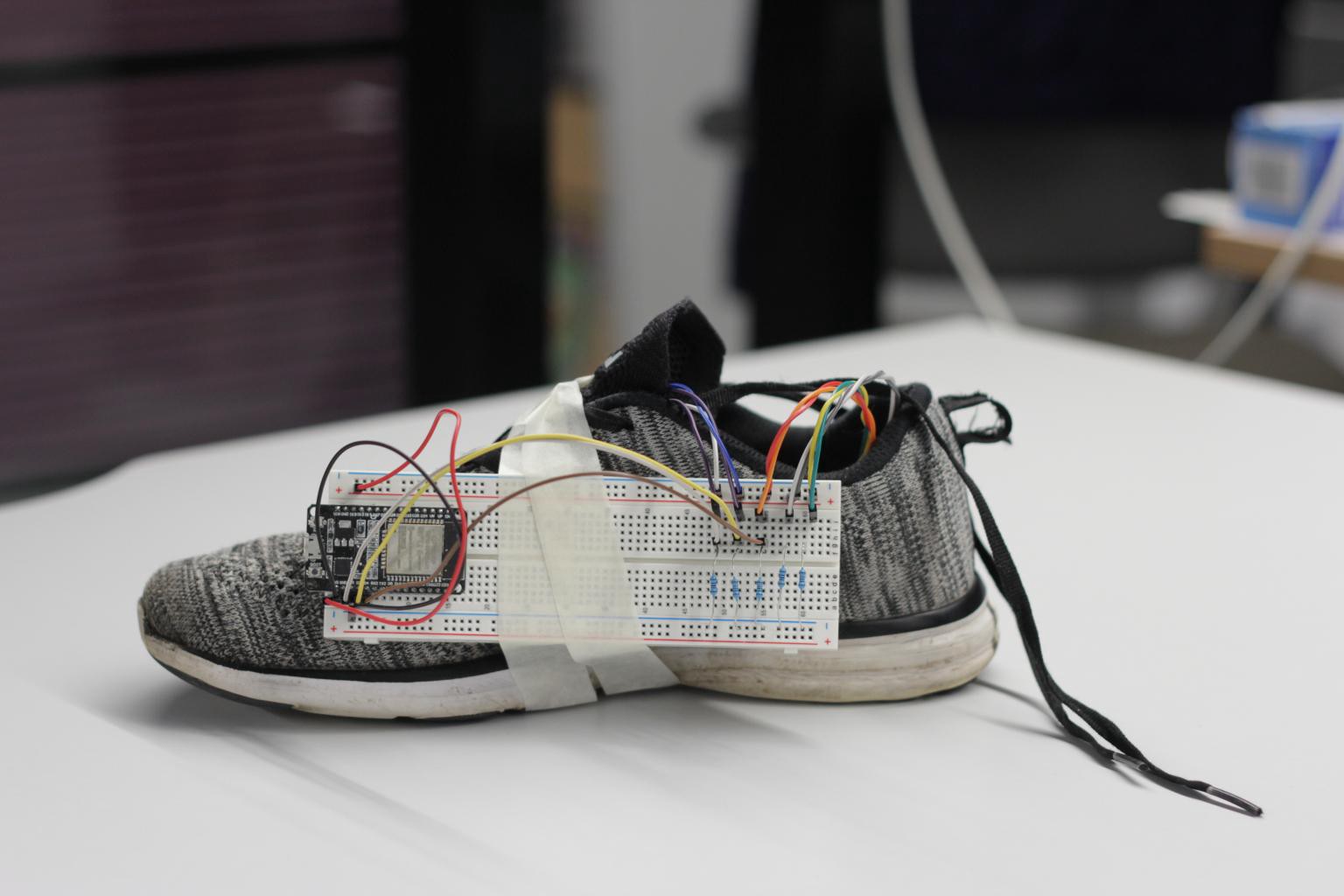

So we started out working with pressure sensors embedded inside an insole. And while that prototype got us off to a good start, and looked sufficiently ridiculous strapped to a shoe when presented at tech meet-ups (remember meet-ups?), it turns out that these pressure sensors are a bit tricky to work with, as connections frequently break and they require a fair bit of extra wiring too. As a result we have pivoted away from pressure, but more on that later.

Socially-distanced hardware hacking

We found ourselves having a bit of time over summer to focus on R&D. Previously I’d been tinkering with this project alone in my ivory tower, but now we needed a ‘proper’ project, which means a Trello board, code reviews, standups and demos. All standard stuff that we don’t need to dwell on.

As a team we’d never done hardware before, but we’ve ran lots of software projects, so “how hard can it be?”.

The first hurdle is that physical components must be selected, purchased and distributed to the team. Not a huge problem, unless you’re in the middle of Russia — oh, I forgot to mention that one of us is in the middle of Russia.

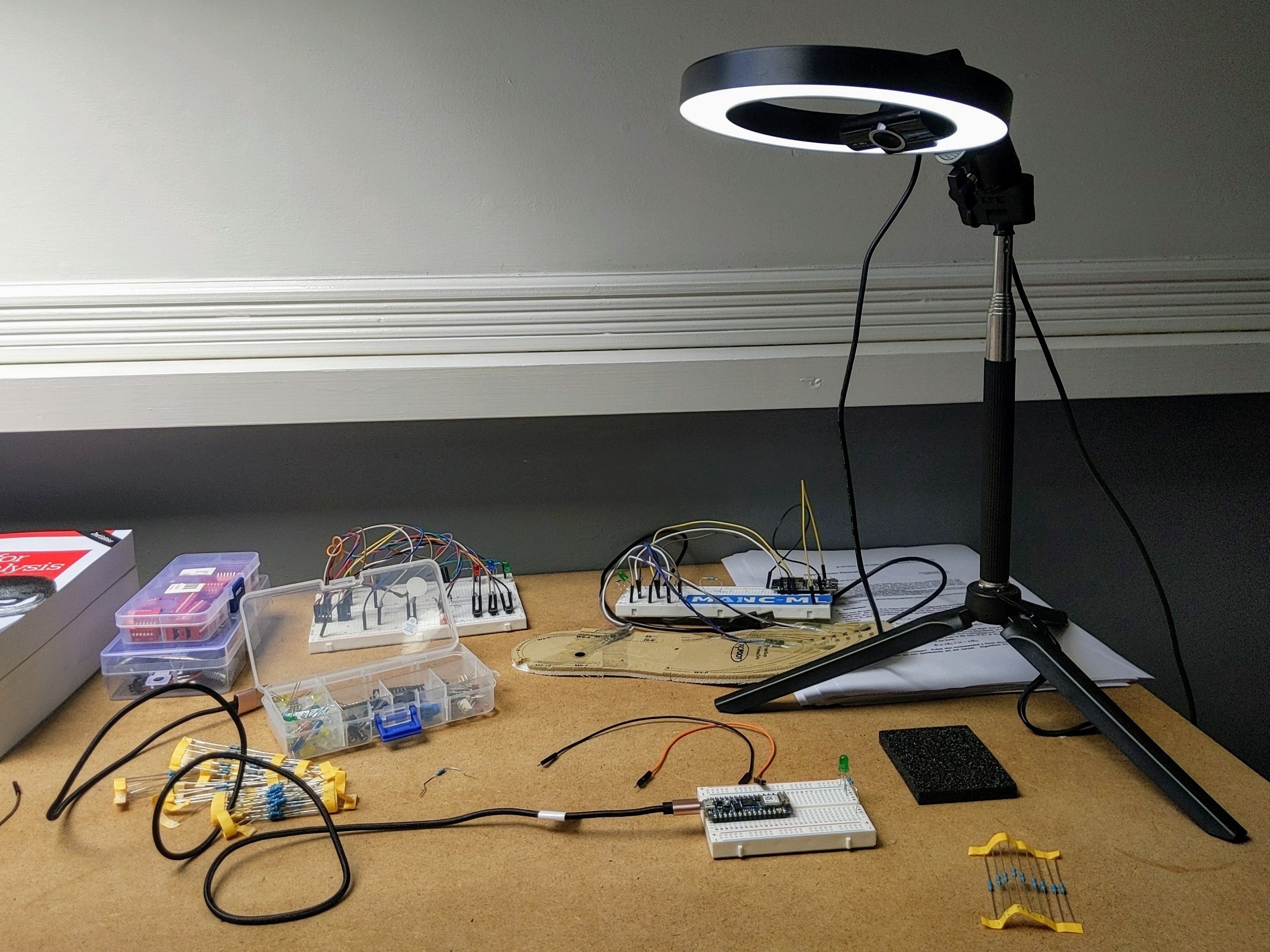

Components bought, next we needed some knowledge transfer. A carefully-balanced webcam meant I could share a top-down view of my desk while talking through the wiring:

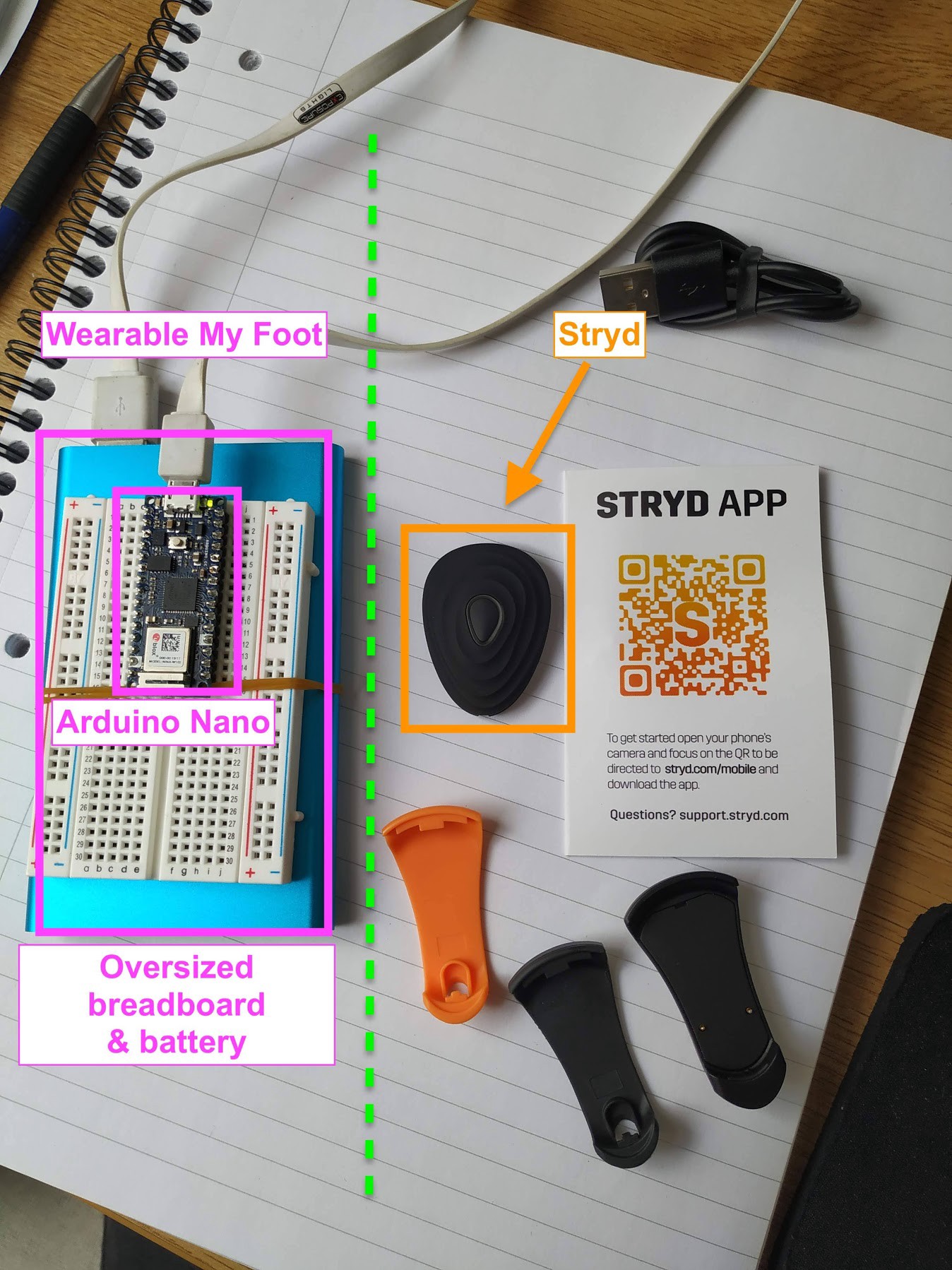

At this point we switched to a smaller microcontroller (Arduino Nano IoT) and smaller breadboard. We really wanted to get this into a small form factor so it could be mounted on the top of the user’s footwear. Similar products on the market, including the Nurvv connect the insole to a discrete box.

We can 3D print a box easily enough, but we also need a custom printed circuit board rather than the bulky breadboards as seen above. A trip to a local PCB assembly firm gave us a few good, inexpensive options (n.b. Coronavirus restrictions were less severe by this time). Meanwhile, we built a step counter using our latest prototype.

A consensus developed that this hardware was too unreliable. The final nail in the coffin came after watching a review of Nurvv and realising that even if we overcame hardware challenges, a smart insole for running has limited use. The reviewer mentioned another product called the Stryd which measures running power using an accelerometer, so we pivoted to trying our our hand (foot?) at something similar.

The quest for power

Cycling power meters are common. These devices directly measure the torque applied at the pedals, which along with rotational speed give us a decent idea of power. For running power the process is less obvious because we can’t measure the leg muscles directly, however commercially-available products like the Stryd are able to work from acceleration alone, and so once again we ask how hard can it be?

Our chosen microcontroller (Arduino Nano IoT), has an inbuilt accelerometer and gyroscope, so no additional hardware is needed. Furthermore, models like EESA offer some promising theoretical grounds for calculating power from foot acceleration.

What followed was a series of experiments that involved collecting real-world data, analysing it, and trying out various techniques to characterise steps, cadence, distance and ultimately power.

Gathering data

We picked on the most athletic of our team, Tom, to gather data, and we sent him out wearing the latest in our line of fashionable prototypes, hot off the soldering station:

The tricky bit is deciding exactly what data to collect. We’d start by coming up with some theory and devising an experiment; for instance we may want to understand how change in elevation is related to change in power output. Next we’d gather example data in the chosen conditions. Finally experiments would be run on the data, inevitably leading us to need even more data. Repeat ad infinitum.

At least we got some exercise!

Analysis and modelling

The physics behind running power isn’t too challenging, at least as far as physics goes. We start from acceleration, recall our calculus lessons, and proceed to plug numbers into formulae. And in an ideal world, we’d be done in time for lunch!

In fact most of the reasons why this is harder than it should be come from tendency of the real world to throw things at us like noise, sampling errors, and imperfect hardware. That, in addition to not always being sure which way gravity points (really).

For a detailed account of some of the analytical work that’s gone into this project, see this wonderful blog post from Misha Iakovlev.

Software development

I’ve mostly discussed the ‘R’ (research) part of ‘R&D’, but we’ve also put a fair bit of effort into development of software to support this project.

At the early stages of a project like this the primary purpose of software is to aid data collection and data preparation. Later on the balance shifts towards end-users. Our first mobile app was a tool for collecting data, but as more capabilities were developed ‘in the lab’, they were incorporated into the app as well.

Because this is an open-source project aimed at nerds, we’re not afraid to add gimmicks and customisations to the app, so as time goes by it will be possible to tweak more and more aspects of the algorithms that this app uses. For now we display cadence, speed and total distance covered.

One particular challenge arose. Without getting too far into the detail, we needed to keep an up-to-date estimate as to the direction in which the user moves.

A good approach is principal component analysis, a common technique that is used to find trends in all sorts of situations. In our case, we’re trying to find a major axis of motion from the accelerometer data — i.e. a clear direction.

It needed to be done in real-time too, updating the estimate over time so that the mobile app could calculate up-to-date metrics for speed and power. Since nothing out there seemed to fit the bill, we released an implementation of online PCA that’s specifically designed to be used in Android apps.

The ever receding finish line

Wearable My Foot is an ongoing R&D project for Fuzzy Labs. It challenges us as a team to learn and it enables us to try out new technologies away from our client work.

Moreover, much of the underlying technology that we’ve developed can be readily repurposed for similar projects involving analytics and machine learning on sensor data. Get in touch to see how we might be able to help with similar projects.

It’s open-source, so if you want to contribute or if you have a novel use case, take a look at the repository on Github.

Finally, we’re on the lookout for talented individuals to join Fuzzy Labs and work with us on exciting projects like this. Take a look here to learn more.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)